Design for Decommission: Why Communities Must Plan Today for Tomorrow’s Infrastructure

Rethinking how data centers and other critical facilities are sited, operated, and transitioned — so communities aren’t left managing unintended consequences decades later.

By Joelle Hushen – President and CEO

A Problem Communities Are Just Beginning to Recognize

Across the country, communities are starting to push back against large data center developments—not because they are anti-technology, but because they are beginning to understand the long-term impacts these facilities can have when planning stops at approval.

In recent months, headlines have celebrated neighborhoods and municipalities that successfully halted proposed data centers, often framing these decisions as victories for local control. What these stories reflect is not a sudden rise in NIMBY sentiment, but a growing awareness that many communities were never fully informed about what hosting this type of infrastructure actually entails.

To the untrained eye, a data center appears deceptively benign: a large, quiet building with few employees and limited traffic. What is less visible—and rarely explained during early planning stages—is how these facilities operate.

Data centers exist to keep digital systems running continuously. Thousands of servers process information around the clock, generating enormous amounts of heat. That heat must be removed constantly to prevent equipment failure, which drives the need for large-scale cooling systems. Depending on design, this cooling can require significant electricity, substantial water use, or both. Even facilities marketed as “efficient” still operate on an always-on model that does not allow for downtime during peak demand.

To maintain uninterrupted service, data centers also rely on redundant power systems. Backup generators—often diesel—are installed on-site and tested regularly. High-intensity security lighting operates throughout the night. Electricity demand can rival that of small cities, and water consumption can place unexpected strain on local supplies.

These demands often extend beyond the footprint of the facility itself. In many regions, utilities must upgrade substations, transmission lines, and other infrastructure to accommodate data center loads. While the data center pays for its electricity usage, the cost of expanding or reinforcing the broader system is frequently distributed across all ratepayers. As a result, nearby residents may see higher utility bills without fully understanding why—or without ever having agreed to host such infrastructure in the first place.

None of this is inherently the result of bad intent. Corporations seek reliability, efficiency, and cost control. Communities seek economic development and growth. The problem arises when long-term operational realities are not clearly communicated, and when responsibility for future impacts is not addressed upfront.

When issues such as noise, lighting, water use, or rising utility costs surface months or years later, communities are left reacting rather than planning. Solutions at that stage are expensive, politically charged, and difficult to implement. Trust erodes, conflict escalates, and opportunities for collaboration are lost.

This pattern is not unique to data centers—but data centers make it impossible to ignore. They expose what happens when infrastructure is approved without a shared understanding of its full lifecycle, and when neither communities nor corporations are equipped to plan beyond the initial build.

What CPTED Already Teaches Us — and Where the Gap Appears

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) has always been concerned with more than crime in the narrow sense. At its core, CPTED addresses how environments influence behavior, how ownership and responsibility are expressed, and how maintenance, visibility, and access shape perceptions of safety and legitimacy over time.

The foundational principles of CPTED—natural surveillance, natural access control, territorial reinforcement, and maintenance—have long emphasized that neglect, ambiguity, and unmanaged space create opportunities for harm. These principles are flexible, adaptable, and capable of addressing a wide range of environments, from neighborhoods and campuses to commercial and institutional settings.

However, in practice, CPTED is most often applied at a single moment in time. It appears during a design review, a security assessment, or a retrofit after problems have already surfaced. The focus tends to be spatial: how a place functions now, how people move through it today, and how risks can be reduced under current conditions.

What is less commonly addressed is time.

CPTED is rarely asked to consider how a place will change, how long a use is likely to remain viable, or what happens when operational realities shift. Transition—whether gradual or abrupt—is often treated as outside the scope of safety planning. Yet transition is precisely when environments become vulnerable: when maintenance declines, ownership becomes unclear, and responsibility is contested.

The gap, then, is not a lack of CPTED principles. It is the absence of intentional, lifecycle-based application of those principles.

Introducing Design for DecommissionTM

Design for Decommission responds directly to this gap by applying CPTED principles across the entire lifecycle of a place, not just its initial design or peak use. It asks planners, designers, developers, and decision-makers to consider safety, stewardship, and community impact from the earliest stages of site selection and approval through operation, transition, and eventual decommissioning or reuse.

“When planning stops at operation, communities inherit the blind spot.”

Design for Decommission is not a new model of CPTED, nor is it a replacement for existing practice. It does not introduce new principles or redefine the framework. Instead, it makes explicit what CPTED has always implied: that safety, legitimacy, and care are not static conditions, but ongoing responsibilities that evolve as places change.

At its core, Design for Decommission asks a fundamental question that is often overlooked:

What happens to this place—and to the surrounding community—when its original purpose changes or ends?

By integrating this question early, Design for Decommission shifts CPTED from a reactive tool to a proactive planning lens. It encourages transparency, anticipates points of conflict, and clarifies responsibility before problems arise. In doing so, it strengthens—not dilutes—the relevance of CPTED in modern, complex environments.

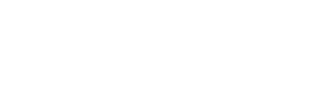

Figure 1. Lifecycle blind spot versus lifecycle planning.

Traditional development models often focus on site selection, construction, and operation — stopping planning at the point of use. Lifecycle planning extends CPTED thinking across the full lifespan of a site, intentionally addressing transition and reuse so that today’s infrastructure does not become tomorrow’s liability.

Why Data Centers Make the Lifecycle Gap Impossible to Ignore

Data centers did not create this problem—but they make it visible in ways few other facilities can.

Unlike many forms of development, data centers are designed to operate continuously, often for decades, with limited public interaction and minimal daily staffing. Their impacts are not concentrated at opening day, nor do they always show up in traditional traffic or land-use metrics. Instead, their effects accumulate over time: persistent noise, round-the-clock lighting, long-term water demand, and sustained pressure on energy infrastructure.

Figure 2. Data center during active operation.

Modern data centers require significant energy, water, and infrastructure investment. When thoughtfully sited and designed, these facilities can coexist with surrounding neighborhoods while strengthening local utility systems and long-term community resilience.

Because these impacts emerge gradually, they are easy to underestimate during early planning and approval stages. Communities may focus on zoning compatibility, tax benefits, or economic development promises without fully understanding what “always-on” infrastructure means in practice. By the time operational realities become clear, the facility is already embedded in the landscape, and meaningful changes require costly retrofits or contentious negotiations.

This is where the lifecycle gap becomes unavoidable.

Data centers force a reckoning with questions that have long been deferred in planning and design:

- Who is responsible when impacts extend beyond the property line?

- How are community costs distributed over time?

- What happens if technology changes faster than land-use plans?

- How do we manage transition—not just construction and operation?

These questions are not unique to data centers. They apply to many forms of modern infrastructure. But data centers compress these issues into a single, highly visible case—making it clear that planning solely for initial use is no longer sufficient.

Design for Decommission emerges here not as a critique of development, but as a response to complexity. It acknowledges that facilities with long lifespans and evolving operational needs demand a different kind of foresight—one that treats transition as inevitable and plans for it from the beginning.

“Data centers are not temporary structures — they are long-term neighbors with long-term impacts.”

What Becomes Possible When We Plan Beyond the Present

When communities and corporations plan only for immediate function, conflict is almost guaranteed. When they plan for transition, something else becomes possible: shared value.

Design for Decommission reframes data centers—and other large infrastructure—not as isolated technical assets, but as long-term neighbors within a community. This shift opens the door to creative, mutually beneficial outcomes that can exist while the facility is operational, not just after it is decommissioned.

Figure 3. Data center in operation — integrated but secured.

When planned intentionally, data centers can strengthen local infrastructure during their operational life, including grid upgrades, enhanced utility capacity, reclaimed water systems, and future-ready energy and heat recovery pathways — while remaining securely separated from surrounding neighborhoods.

For example, the infrastructure required to support a data center can strengthen systems the community already depends on. When electrical upgrades are designed with shared resilience in mind, surrounding neighborhoods may benefit from a more stable grid and faster power restoration—similar to the advantages often seen near hospitals or emergency facilities. When water systems are modernized to support cooling demands, those improvements can reduce losses, improve efficiency, and create opportunities for expanded reclaimed water use for irrigation or other non-potable needs.

These benefits do not happen automatically. They require intentional planning, early dialogue, and clear agreements about responsibility and long-term stewardship when discussed early in the planning process. But when they are part of the conversation from the start, data centers can become catalysts for infrastructure improvements that outlast their original purpose.

Equally important is how facilities relate to their surroundings during their operational life. Thoughtful landscape design, lighting strategies that minimize spillover, noise mitigation treated as a design priority rather than a complaint response, and transparent communication channels all help integrate these facilities into the fabric of the community. Even when a data center remains highly secure and largely inaccessible, it does not have to feel disconnected or adversarial.

Looking further ahead, planning for decommissioning and reuse expands the range of possibilities even more. A facility designed with future adaptation in mind is easier to repurpose, less likely to become a liability, and better positioned to serve community needs once its original function ends. The long operational timeline—often ten to fifteen years or more—becomes an opportunity rather than a delay: a period during which trust can be built, infrastructure strengthened, and shared goals clarified.

“Design for Decommission is not about limiting development — it’s about planning responsibly for what comes next.”

Design for Decommission does not ask communities to accept unchecked development, nor does it ask corporations to absorb unlimited responsibility. Instead, it offers a framework for collaboration—one that recognizes that safety, trust, and resilience are built over time, not imposed after the fact.

Shared Responsibility: Planning Together for Long-Term Outcomes

When communities and corporations plan for transition from the beginning, the question of “what happens next” becomes an opportunity rather than a liability. Facilities designed with future adaptation in mind can later support workforce training centers, innovation hubs, municipal operations, emergency response facilities, or light industrial uses, depending on community needs. With thoughtful design, surrounding land can transition into green space, community infrastructure, or mixed-use development that reconnects the site to the neighborhood it once stood apart from.

Even before full repurposing occurs, interim uses can help soften the boundary between facility and community—through shared infrastructure, environmental buffers, or adjacent uses that provide public benefit without compromising security. The key is not predicting a single outcome, but preserving flexibility so the site can evolve as community needs change.

What This Means for the Future of CPTED

Design for Decommission does not signal a departure from CPTED’s foundational principles. It reinforces them.

As environments become more complex, more technical, and more long-lived, the need for CPTED does not diminish—it expands. The principles of natural surveillance, access control, territorial reinforcement, and maintenance remain as relevant as ever, but their application must extend beyond a single moment in time.

CPTED has always understood that neglected, ambiguous, or unmanaged spaces create risk. Design for Decommission simply asks practitioners to recognize that transition itself is a vulnerable condition—one that deserves the same level of intentional planning as initial design or active use.

Figure 4. Repurposed data center as a long-term community asset.

When future reuse is considered from the start, former data center sites can transition into community-serving spaces — such as innovation hubs, educational facilities, public services, or mixed-use centers — supported by existing utility capacity, resilient infrastructure, and thoughtful design integration.

By incorporating lifecycle thinking into CPTED practice, professionals gain a stronger role in conversations that traditionally occur outside the scope of safety and design review. Questions about site selection, infrastructure capacity, long-term responsibility, and future reuse become part of the CPTED dialogue—not after problems arise, but before decisions are finalized.

This approach positions CPTED practitioners not as late-stage problem-solvers, but as early-stage collaborators—helping communities and organizations navigate complexity with foresight, transparency, and shared accountability.

In this way, Design for Decommission reflects the broader CPTED movement itself: a shift toward deeper collaboration, expanded relevance, and a renewed focus on how environments support safety, trust, and well-being over time.

Looking Forward: Designing for Change, Not Just Use

Modern communities are no longer shaped by static places. Technology, infrastructure, and land use are evolving faster than traditional planning cycles can accommodate. Facilities that once seemed permanent may change function within a generation, while their physical and social impacts endure far longer.

Design for Decommission invites a different mindset—one that accepts change as inevitable and plans for it intentionally.

Rather than asking communities to choose between progress and protection, or asking organizations to absorb risk after conflicts arise, this approach creates space for shared problem-solving. It encourages early dialogue, creative integration, and long-term stewardship that benefits both sides.

When applied thoughtfully, Design for Decommission allows places to evolve without becoming liabilities. It supports communities in advocating for transparency and resilience, and it helps organizations reduce conflict, protect investment, and build trust that extends beyond a single project lifecycle.

CPTED has always been about more than preventing harm. It has been about creating environments that communicate care, responsibility, and legitimacy. Extending that commitment across time—through planning for transition, reuse, and change—is not a reinvention of CPTED. It is a reaffirmation of its purpose.

“When communities and developers plan together across the full lifecycle, infrastructure can evolve from necessity into lasting community value.”

The conversation around data centers is only the beginning. As communities and industries continue to navigate increasingly complex environments, Design for Decommission offers a path forward—one grounded in foresight, collaboration, and the enduring principles that have always guided safer design.

Planning for reuse and transition allows places that once felt closed or disconnected to eventually become integrated, productive parts of the community fabric—reinforcing the idea that good design does not end when a use does.

Joelle Hushen – President and CEO

Joelle Hushen, as the Executive Director of the NICP, Inc., is responsible for course curriculum, standards, and evaluation. This includes the development and maintenance of the NICP’s CPTED Professional Designation (CPD) program, which has become the recognized standard for CPTED professionals. As part of the CPD program Joelle designed the CPTED Review, Exam, & Assessment Course and is the lead instructor.

Joelle has a background in education and research with a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of South Florida. She has completed the Basic, Advanced, and Specialized CPTED topics, and holds the NICP, Inc.’s CPTED Professional Designation. Joelle is a member of the University of South Florida Chapter of the National Academy of Inventors, and the Florida Design Out Crime Association (FLDOCA).

Ready to Earn Your CPTED Certification?

Take the next step toward becoming a CPTED professional. Our in-person and online training options will prepare you to assess environments, apply proven CPTED strategies, and earn your CPD designation. Learn how to design safer, more livable spaces that strengthen communities and reduce crime before it happens.