Safety is Becoming the Next Global Movement: Framework for the Future of Safety in the Built Environment

By Joelle Hushen – President and CEO

A Shift Begins

At a recent industry event hosted by the Secure Buildings Council in New York, a short panel discussion caught my attention. The topic was simple but revealing: safety in the built environment is shifting from an amenity to an expectation.

Listening to the conversation, I realized something many of us have sensed emerging for years:

People no longer view safety as a bonus feature. They expect it. And increasingly, they are choosing where to live, work, study, and gather based on whether a space feels right.

This shift is not subtle.

It reflects a deeper cultural movement taking shape — one with striking parallels to the early days of sustainability.

What began as a desirable upgrade is rapidly becoming a baseline requirement.

For years, safety was handled quietly and reactively. It lived in the background, referenced in codes, delegated to specialists, or addressed only after something went wrong. Most people didn’t think about the design of safety unless they needed to — and by then, it was often too late to influence the environment itself.

But something has changed in recent years.

Awareness has risen. Expectations have sharpened.

People recognize, even if they can’t always articulate it, that environments play a central role in how safe, welcome, and at ease they feel.

This is more than public concern and more than anxiety about crime.

It is a new cultural expectation taking root — a belief that the places we inhabit should feel clear, coherent, and supportive, not confusing, isolating, or stressful.

Expectation becomes demand.

Demand becomes movement.

And movement is what transforms standards into requirements.

We are at the beginning of that movement now.

People Are Feeling the Change Before They’re Naming It

The most striking part of this shift is that people are sensing it long before they’re articulating it.

Most individuals don’t use terms like sightlines, access points, or visibility. They don’t talk about spatial legibility, glare, or intuitive movement. They simply know when a place feels right — and when it doesn’t.

They pause before walking into a dim corridor.

They choose one parking area over another without knowing why.

They pick cafés, parks, workplaces, and campuses that feel open, welcoming, and easy to navigate.

And they avoid spaces that feel confusing, exposed, or isolating — even if nothing “bad” has ever happened there.

This isn’t driven by fear.

It’s driven by instinct.

Human beings read environments with their bodies before their minds catch up. Our nervous system responds to openness, lighting, clarity, and the presence of other people long before we consciously process any of it.

A place that feels coherent allows us to settle. A place that doesn’t causes us to speed up, disengage, or withdraw.

When people say, “I just don’t like the feel of that place,” there is almost always a real environmental reason behind it — even if they can’t identify it. And when they say, “I love spending time here,” there is usually a set of supportive design conditions at play.

This is why so many people who take a CPTED course say the same thing afterward:

“I can’t unsee it now.”

The principles were always there — they simply didn’t have the language.

And now, without knowing the terminology, the general public is beginning to expect environments to support comfort, clarity, visibility, and ease.

That is the early stage of a cultural shift:

People aren’t just noticing the difference — they’re beginning to expect it.

Why This Shift Is Happening Now

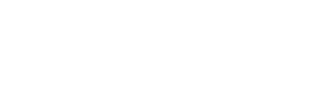

Cultural transformations rarely happen overnight. They build slowly, gathering momentum as different forces begin pointing in the same direction. That is what we are seeing now with safety in the built environment: multiple pressures, motivations, and expectations aligning at once — often without coordination, but with unmistakable convergence.

Several factors are driving this shift.

First, public awareness is higher than ever.

People are paying closer attention to how environments shape their daily experience — whether they feel comfortable walking to their car at night, whether their child’s school feels open or confusing, or whether a workplace feels coherent and supportive. These instincts are not about fear; they are about clarity, comfort, and belonging.

Second, insurers and liability carriers are scrutinizing environments with new intensity.

Buildings and campuses that lack proactive, design-supported safety measures face greater exposure and higher premiums. What used to be considered “nice to have” is increasingly seen as a matter of risk and responsibility.

Third, tenants and employees are reshaping the demand curve.

The places people choose — and the places they leave — increasingly reflect how environments make them feel. Organizations track this through turnover, satisfaction, engagement, and reputation. Environments that support comfort, visibility, and intuitive movement simply perform better.

Fourth, owners and investors have noticed.

Safety is no longer framed as an operational expense or hardware decision. It is a measure of value, resilience, and long-term viability. Spaces that feel coherent and supportive attract and retain people; spaces that do not, struggle.

And fifth, the design and security professions themselves are evolving.

For decades, these fields operated in parallel silos — architects focused on form and function, planners on policy and flow, engineers on precision, and security professionals on risk mitigation. Safety was often bolted on at the end rather than shaped from the beginning.

Today, that model is evolving and integrating.

Projects are too complex, technology too intertwined, and expectations too high for safety to remain an afterthought. Designers, planners, engineers, and security professionals are increasingly recognizing that they are each working on different parts of the same human experience — but without a shared framework or vocabulary to guide that integration.

That gap is now becoming visible. And it’s one of the strongest signs that a broader movement is forming:

the need for a unifying, people-centered philosophy that connects safety to design, behavior, and community life.

This cultural shift resembles the early days of the sustainability movement, when environmental concerns moved from the margins into the mainstream. Sustainability captured momentum once people understood that environmental health shaped personal well-being, economic viability, and long-term resilience — not just ecosystems.

Now, something similar is happening with safety.

People are beginning to see that environments shape stress, comfort, behavior, and even community life. Safety is no longer the domain of specialists; it is part of everyday experience.

What once felt like a niche consideration is becoming a widespread expectation — the early stage of a movement.

The Changing Relationship Between People and Place

The relationship between people and the built environment is changing.

For a long time, safety was understood as something that lived outside of design — the realm of hardware, procedures, and specialist expertise. Design shaped how a place looked and functioned; safety shaped how it was monitored and controlled. The two operated in parallel, sometimes intersecting, but rarely integrated.

But as expectations shift, people are experiencing safety differently.

They are noticing — consciously and unconsciously — how environments influence their comfort, awareness, movement, and sense of belonging. They are recognizing that design is not neutral: it affects stress levels, decision-making, social behavior, and the ability to relax or connect with others.

This awareness isn’t limited to any single profession.

Across planning, design, engineering, and security, the old technical silos are breaking down. These fields are beginning to see that they have been working on different aspects of the same human experience — yet without a shared philosophy or vocabulary to bring those pieces together.

As a result, safety is no longer understood as a reactive layer added at the end of a project. It is becoming something shaped from the beginning — through the quality of movement, the clarity of a space, the visibility between people, and the cues that communicate whether an environment is cared for and welcoming.

And just as important, people are placing higher value on environments that support connection — places where they feel part of something rather than isolated from it.

Belonging has become a safety signal of its own.

When a space invites people in, affirms their presence, and reflects care in its design and upkeep, it communicates that the community is paying attention. It tells people they matter.

When environments support natural flow, clear sightlines, intuitive boundaries, and positive interaction, people feel more at ease. They settle. They slow down. They participate in the space rather than withdraw from it. And when environments work against these conditions, people sense it immediately, even if they cannot explain why.

This is the deeper transformation underneath the cultural shift:

People are not simply asking, “Is this place safe?”

They are asking, “Does this place support how I live, move, feel, connect, and belong?”

That change in perception is reshaping how communities experience the built environment — and it is laying the groundwork for a broader movement to emerge.

Why Expectations Are Rising All at Once

The rise in safety expectations may feel sudden, but it has been building beneath the surface for years. What we are seeing now is the point where several cultural, economic, and social forces are converging — each reinforcing the others.

People are more attuned to the environments they move through.

After years of rapid social change, uncertainty, and shifts in how and where people work, many have become more aware of whether spaces support or hinder their well-being. Environments that once went unnoticed are now being evaluated through a different lens:

Does this place make sense? Does it help me feel grounded? Does it feel cared for?

Organizations are reevaluating the environments they create.

Companies, schools, healthcare systems, and public institutions understand that physical space influences performance, engagement, and trust. A workplace that feels chaotic or isolating doesn’t just affect productivity — it affects retention, reputation, and the willingness of people to return.

Communities are prioritizing well-being and connection.

This moment has reminded people of the importance of belonging, shared spaces, and environments that support positive activity. And in this context, “community” doesn’t refer only to residential neighborhoods — it includes workplaces, campuses, cultural spaces, parks, transit systems, and anywhere people share environment and experience.

All of these settings shape whether people feel part of something larger or disconnected from one another.

And beneath all of this is something deeply human: people want environments that help community life flourish, not erode it.

Technology and transparency have changed expectations.

People are more informed than ever about how environments function. They compare experiences across cities, workplaces, schools, and public spaces. Good design no longer feels like an upgrade — it feels like a baseline.

And importantly, safety concerns have become part of everyday life — not in a fearful way, but in a practical one.

People expect spaces to support visibility, clarity, and ease of movement. They expect environments to reduce unnecessary stress and avoid designs that isolate, confuse, or overwhelm.

All of these forces have combined to create a new cultural baseline:

People expect environments to feel supportive, intuitive, and human-centered — not just functional.

This collective shift is not driven by a single trend.

It is the result of years of quiet momentum that have now reached a tipping point.

The Embodied Experience of Safety

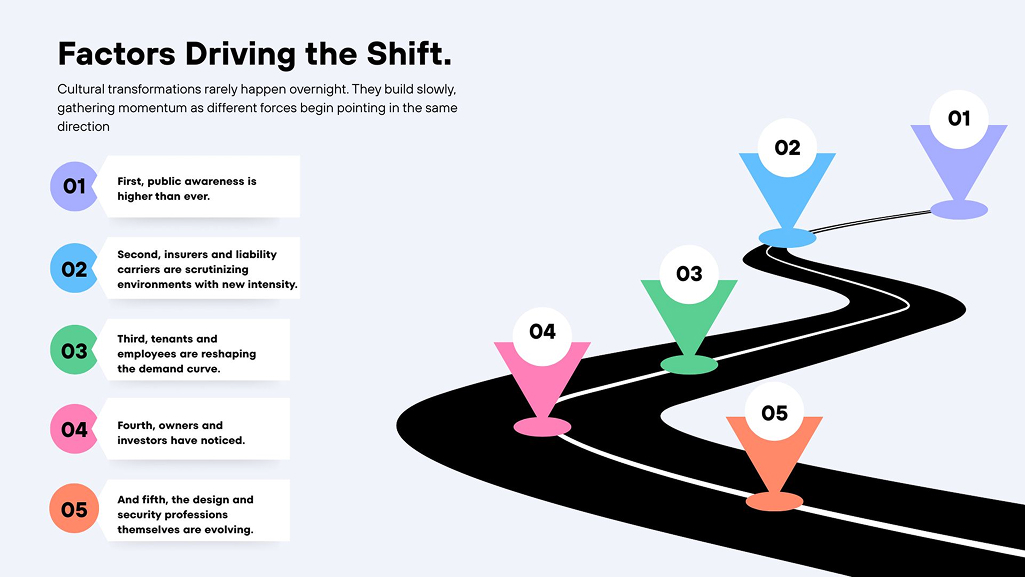

One of the clearest signs that safety is becoming a cultural expectation is that people are responding to environments with their bodies long before they form conscious judgments. This is not about fear — it is about how human beings are wired.

Modern research has made this unmistakably clear:

People don’t just think about safety. They feel it.

Our nervous system takes in information about a space — light, openness, sightlines, movement paths, density, sound, maintenance — and forms a rapid physical response. We relax or tense. We slow down or speed up. We lean in or withdraw. We choose to linger or to move through as quickly as possible.

Most people don’t use the vocabulary of design to describe this.

But they know the feeling of a place that supports them — and the feeling of a place that doesn’t.

A space with clarity and openness creates ease.

A space that is confusing or constricting creates stress.

A well-lit walkway can feel calming and predictable.

An over-lit or unevenly lit area can feel disorienting or uncomfortable.

A plaza with natural flow invites people to gather.

A corridor that bottlenecks movement increases tension for everyone in it.

In other words, environments shape our physiology — not the other way around.

This is the deeper layer of the shift happening now:

People are becoming more aware of what their bodies have always known.

They are recognizing that safety is not only the absence of risk; it is the presence of clarity, predictability, coherence, and connection.

This embodied dimension of safety is what some fields have always understood intuitively — even before neuroscience and behavioral research caught up. It’s the recognition that environments influence how people feel about themselves and one another, and how those feelings guide behavior, interaction, and community life.

When people describe the places where they feel most comfortable, they are describing environments where fundamental design principles are already working:

spaces that are easy to navigate, where movement makes sense, where boundaries are clear without being restrictive, where people can see what’s happening around them, and where the environment itself signals care.

This recognition is part of why expectations are rising.

People are beginning to trust their bodies — and question environments that work against them.

And as this shift becomes more widespread, it is reshaping how society understands what safety actually is:

not control, not surveillance, not restriction,

but an environment that helps people feel grounded, aware, connected, and able to thrive.

And increasingly, people are discovering that this kind of safety isn’t accidental — it comes from deliberate choices in how places are designed and cared for.

Reintroducing CPTED: The Human-Centered Framework Behind the Shift

If safety is becoming a cultural expectation, then the next natural question is this:

What philosophy can guide this shift in a way that supports people — not restricts them?

For decades, that framework has existed.

It simply hasn’t been clearly understood outside certain professional circles.

It’s called Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, or CPTED.

CPTED emerged in the 1970s as a simple but powerful idea:

our environments influence how we feel, how we move, and how we behave.

Good design can reduce opportunities for crime, encourage positive interaction, and strengthen a sense of belonging. Poor design can do the opposite.

Today, CPTED sits at the intersection of design, planning, behavioral science, and community life — offering a shared language that helps architects, planners, engineers, security professionals, and operators work together without operating in silos.

It provides something the industry has lacked for decades: a shared vocabulary for solving complex safety and design challenges without talking past one another.

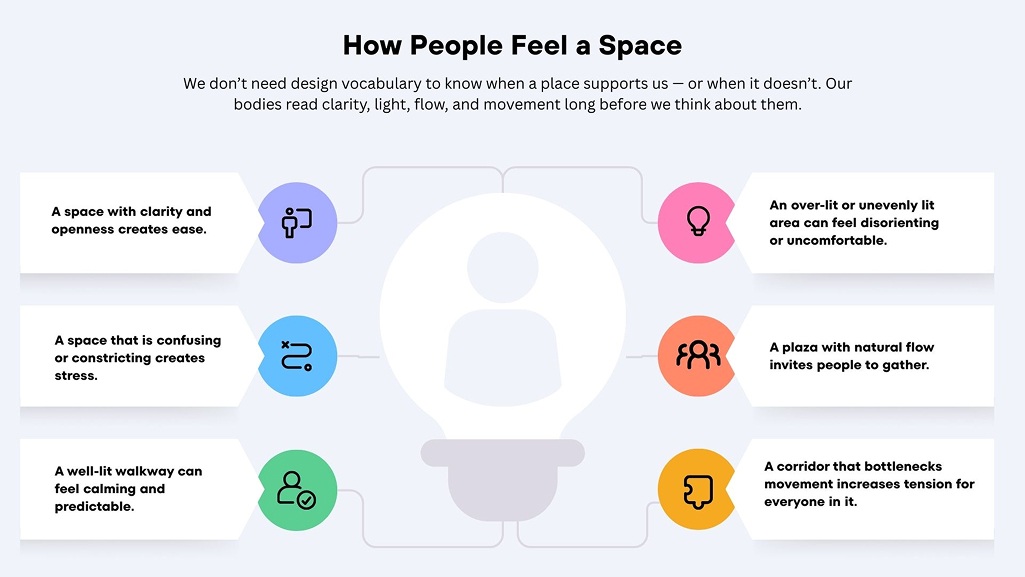

But before going further, one clarification is essential:

CPTED is not hostile architecture.

It is not about exclusion, discomfort, or punishment.

It is not benches with dividers, spikes on ledges, defensive landscaping, or designs intended to drive people away.

Those tactics violate the foundational principles of CPTED — yet they are often mislabeled as CPTED, creating harmful misconceptions.

True CPTED is the opposite.

It is inclusive design.

It supports positive use rather than restricting presence.

It respects dignity and access.

It helps people feel safe without ever feeling controlled.

It strengthens trust between communities and the places they inhabit.

You can see this in the way the most welcoming shared spaces function.

Think about the kinds of places people move through every day — schools, workplaces, community centers, campuses.

The ones that feel the best are usually the ones where circulation makes sense, gathering areas feel welcoming, and people can see and understand what’s happening around them.

That feeling of comfort isn’t accidental.

It comes from design choices that support ease of movement, positive interaction, and a sense of being grounded throughout the day.

At its core, CPTED focuses on four universally understood concepts:

- Visibility

- Access and movement

- A sense of ownership and care

- Maintenance and stewardship

Simple ideas. Profound outcomes.

These principles shape the places where people feel comfortable, grounded, connected, and welcome — the very qualities people are beginning to expect from their environments.

And this is why CPTED is becoming more relevant than ever:

as expectations rise, organizations need a framework to meet them — one that is grounded in human experience, backed by research, and flexible enough to support different contexts, cultures, and communities.

CPTED provides that framework.

It is becoming the bridge between design and security, between function and feeling, between individual experience and community well-being.

In other words, CPTED is not just part of the safety movement —

it is one of the reasons the movement is emerging at all.

The Early Signals of Requirement

Cultural shifts become movements when they begin shaping systems.

And movements become transformative when those systems start shifting in response.

That is what we are seeing now with safety in the built environment.

People’s expectations are rising, and the systems that shape our environments — design, real estate, operations, security, policy, and investment — are starting to respond.

You can see the shift first in the market pressures surrounding buildings and public spaces. Insurance and liability carriers are reassessing risk with new scrutiny. Environments without proactive, design-supported safety measures are facing higher premiums and greater exposure. What was once a best practice is quickly becoming a financial imperative.

At the same time, tenants, employees, families, and visitors are reshaping the demand curve. They may not use design terminology, but they gravitate toward spaces that feel coherent, intuitive, and supportive — and avoid those that do not. Organizations track these patterns in turnover, satisfaction, engagement, and reputation. What once looked like optional amenities now functions as baseline expectation.

Owners and investors have taken notice. Safety is no longer a line-item cost; it is a measure of performance, trust, and long-term value. Properties designed for clarity, comfort, and positive behavior simply perform better. They attract, retain, and support people more effectively — and the market rewards that.

Meanwhile, the design and security fields themselves have evolved. The old model of retrofitting safety at the end of a project is no longer feasible. Buildings are too complex, technology too interconnected, and user expectations too high for safety to be an afterthought. Integration has become the norm — and CPTED is the framework that brings coherence to that integration.

These operational pressures are accompanied by early signs of formalization.

ISO has begun preliminary work on design-supported safety guidance.

Municipalities are experimenting with CPTED ordinances.

Lighting standards continue to evolve through IES, and in some regions, DarkSky International initiatives. The Secure Buildings Council’s SHIELD program reflects a growing recognition of the relationship between safety, design, and operational readiness.

None of these frameworks are universal — not yet.

But they share a trajectory.

They are early indicators of a transition from expectation to requirement.

This pattern mirrors what we saw in the early stages of the sustainability movement:

behavior shifts first,

certifications emerge next,

policy follows culture.

Across cities, campuses, workplaces, and public spaces worldwide, people are responding in similar ways: they expect environments that help them feel oriented, supported, and connected — with clearer movement paths, intuitive wayfinding, and gathering areas that feel welcoming rather than stressful.

There is another signal as well — one grounded in practice rather than policy:

When environments support positive interaction and remove low-level friction points that generate frequent but preventable incidents, public safety teams face fewer reactive demands. This doesn’t diminish their importance — it strengthens it. It gives officers and security personnel the breathing room to focus on relationship-building, community engagement, and proactive support.

Good design does not replace public safety teams.

It supports them.

Together, these cultural, financial, operational, and organizational pressures point toward a clear reality: safety is becoming something organizations must demonstrate, not simply promise.

What we are witnessing is the early architecture of a new standard — one built not on fear, but on the understanding that environments shape behavior, well-being, and community life.

This is how a movement begins to take structural form.

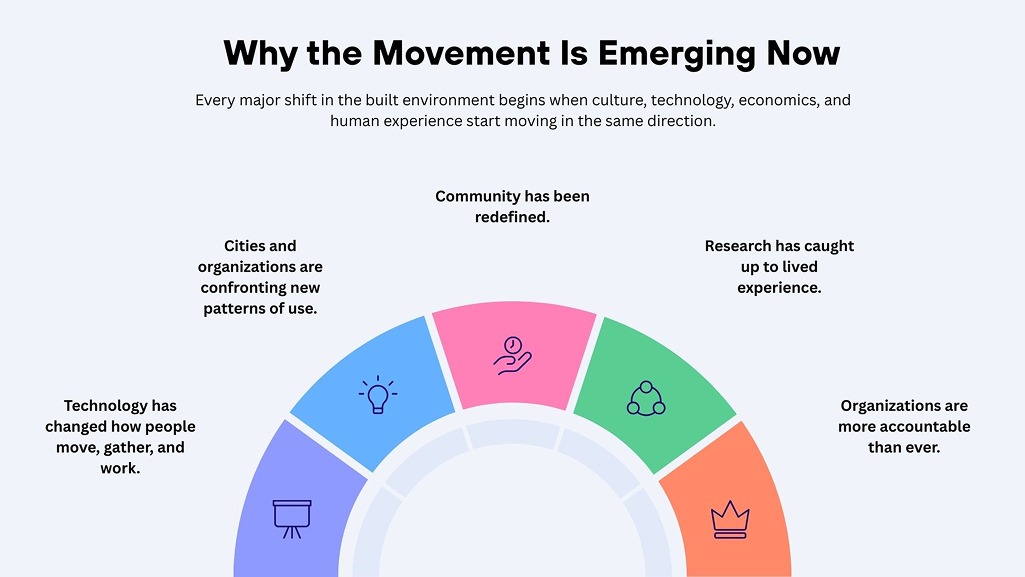

Why the Movement Is Emerging Now

Every major shift in the built environment begins when culture, technology, economics, and human experience start moving in the same direction.

That pattern defined the rise of the sustainability movement, and today, it is defining the rise of the safety movement.

For decades, safety was treated as a background obligation — something handled through compliance, hardware, or incident response. Sustainability, by contrast, captured imagination. It offered a vision of progress, responsibility, and shared purpose. It felt aspirational.

Safety rarely did.

But that is changing.

People are increasingly evaluating their environments not only for what they look like, but for how they make them feel. The embodied experience of safety — feeling oriented, supported, grounded, and connected — is no longer something people hope for. It’s something they expect.

And once expectations shift, industries follow.

Several forces are converging to make this moment possible:

Technology has changed how people move, gather, and work.

Hybrid work, flexible schedules, and the blending of digital and physical environments have made clarity, coherence, and intuitive movement far more valuable than they once were.

Cities and organizations are confronting new patterns of use.

Public spaces host more activities, more fluidly, with fewer predictable routines. The places people once moved through passively are now places they actively assess.

Community has been redefined.

People notice whether environments support connection or make it harder. They gravitate toward places that feel cared for, inclusive, and welcoming — and they avoid places that work against their nervous system.

Research has caught up to lived experience.

Behavioral science, public health, neuroscience, and design research all point to the same conclusion: environments shape well-being, stress, interaction, and trust.

Organizations are more accountable than ever.

The public expects safety to be demonstrated, not declared. Investors, insurers, and tenants reinforce the expectation.

You can see this shift clearly in places designed for learning.

Schools across the country are rethinking hallways, gathering areas, outdoor spaces, and circulation patterns — not to restrict students, but to create environments where young people feel supported, grounded, and able to breathe throughout the day. When these spaces work well, behavior improves, stress decreases, and students describe feeling more connected to their environment and one another. The stakes are different, but the principle is the same: when a place supports people, people respond.

This is also why CPTED is finding its cultural moment.

For decades, its principles emphasized visibility, clarity, natural movement, positive behavior, and community engagement — but only now are people beginning to see these not as security measures, but as qualities that make a place feel welcoming, humane, and intuitive.

In other words, CPTED is helping safety make the same transition sustainability made:

from obligation to aspiration.

Safety is no longer viewed as a constraint, a cost, or an afterthought.

It is becoming something people associate with dignity, belonging, and the ability to participate fully in community life.

This shift mirrors the moment when sustainability transformed from a niche concern to a global movement — not because someone mandated it, but because people recognized its role in shaping a livable future.

Safety is now standing at that same threshold.

And the built environment is beginning to respond.

What Comes Next

Movements don’t begin with regulation.

They begin with recognition — the moment when society realizes that something fundamental has shifted and can no longer be ignored.

That is where safety now stands.

For the first time in decades, the conversation about safety is no longer confined to specialists or hardware decisions. It is taking place in design studios, school districts, corporate boardrooms, community organizations, tech companies, public health agencies, and city halls. The idea that safety should be built into the environment — not added onto it — is becoming a shared expectation.

The implications are enormous.

A safety movement rooted in human experience has the potential to reshape the built environment just as profoundly as sustainability did. It can bring clarity, predictability, and well-being into everyday spaces. It can strengthen trust. It can help communities feel more connected to the places they share. And it can elevate design from meeting minimum standards to creating environments where people genuinely feel they belong.

The design and security fields are already moving toward one another. CPTED provides the framework, the language, and the philosophy to guide that integration. But the movement will not depend on any single profession. It will depend on collaboration — on architects, planners, engineers, educators, operators, developers, public safety teams, and community members working from a common understanding of what people need to feel grounded and supported where they live, work, learn, and gather.

As these expectations continue to grow, the systems around them will catch up.

Certifications will refine.

Guidelines will expand.

Policies will adapt.

Requirements will emerge.

And the movement will gain structure — not because it is mandated, but because it is wanted.

This is how transformation happens.

The next global movement in the built environment will not be defined by technology alone, or by regulations, or by new forms of infrastructure.

It will be defined by something simpler and more powerful: the belief that people deserve environments that help them feel safe, connected, and able to thrive.

Safety is becoming a cultural value.

And the built environment is beginning to answer.

The places we build next won’t just shape our future — they will reflect what we value most.

Joelle Hushen – President and CEO

Joelle Hushen, as the Executive Director of the NICP, Inc., is responsible for course curriculum, standards, and evaluation. This includes the development and maintenance of the NICP’s CPTED Professional Designation (CPD) program, which has become the recognized standard for CPTED professionals. As part of the CPD program Joelle designed the CPTED Review, Exam, & Assessment Course and is the lead instructor.

Joelle has a background in education and research with a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of South Florida. She has completed the Basic, Advanced, and Specialized CPTED topics, and holds the NICP, Inc.’s CPTED Professional Designation. Joelle is a member of the University of South Florida Chapter of the National Academy of Inventors, and the Florida Design Out Crime Association (FLDOCA).

Ready to Earn Your CPTED Certification?

Take the next step toward becoming a CPTED professional. Our in-person and online training options will prepare you to assess environments, apply proven CPTED strategies, and earn your CPD designation. Learn how to design safer, more livable spaces that strengthen communities and reduce crime before it happens.